Cooper’s letter makes the case for allowing inoculation as a legitimate means to avoid suffering and preserve life. In response to opposition, a Bostonian pastor by the name of William Cooper wrote a pastoral letter entitled A reply to the objections made against taking the small pox in the way of inoculation from principles of conscience. Mather also faced violence as a bomb was thrown through the window of his house on November 13, 1721, with the attached note: “Cotton Mather, you dog, dam you! I’ll inoculate you with this and a pox to you.” 3 Multiple pastors preached against it, such as William Douglass who condemned those who received inoculation as being guilty of a sinful distrust of God, though he would change his mind in later years. Despite these tactics, it is surprising to note that Increase Mather did not want anyone to receive inoculation contrary to conscience, but instead for them to be persuaded to change their minds.Īs inoculation was first introduced, there was significant opposition in the medical community and in the church. He caricatured those who were “fierce Enemies to Inoculation” as “Children of the Wicked one.” Instead of being associated with such persons, he argued for his audience to join with such worthy persons as himself and the other pastors who supported inoculation, which included Solomon Stoddard of Northampton. While equating “You shall not murder” to “get inoculated,” he resorted to using shame and attacking the reputation of those who opposed inoculation. 2 In this work the elder Mather sought to discredit the death of an inoculation patient, and argued that inoculation was a way of keeping the sixth commandment. The same year that Cotton Mather began inoculations in Boston, his father Increase Mather published a pamphlet entitled Several Reasons Proving that Inoculating or Transplanting the Small Pox is a Lawful Practice, and that it has been Blessed by GOD for the Saving of Many a Life.

Inoculation Controversy: Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards, and John Newton 1 Though inoculation protected most of those who received it, this success came at the price of human life, as a few of those who were sickened through inoculation died. Among those who were inoculated, the mortality rate dropped to 2 percent. Among those who were not inoculated, the mortality rate was 15 percent. This would result with the inoculated patient being sickened, though usually with a less severe case of the smallpox.

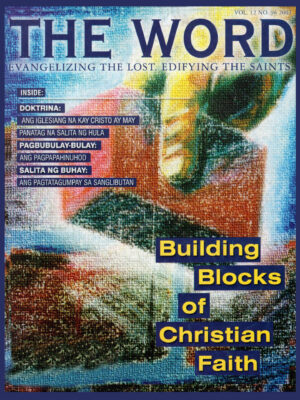

#The word of faith magazine skin

A sample would be taken from someone who was sick, a small cut would be made in the skin of the one to be inoculated, and the sample would then be rubbed into the cut. The method used by Boylston would deliberately infect healthy persons with a live smallpox virus. Mather convinced one doctor by the name of Zabdiel Boylston to begin inoculations.

It was in the midst of this public health crisis that Cotton Mather began to promote an experimental inoculation that he had learned about from his slave Onesimus. This epidemic would take 844 lives before it came to an end. When the epidemic began, the population of Boston was about 11,000, and many fled with their families to escape the disease. With that in mind, let us look three centuries backward to review how the church responded to the smallpox inoculation controversy of 1721.Īs a smallpox epidemic arrived in Boston in the 1720s, whether or not to receive inoculation became the controversy of the hour. As mandates multiply across society, how should one respond? Should those who have previously declined vaccination pursue a religious exemption, or should they get vaccinated? What should one do if there is no religious exemption? As these questions come to the forefront, it is important that we consider how the church has applied Scripture to navigate similar issues in the past. Over this past week, multiple people inside and outside the church have asked about navigating matters of conscience and healthcare when it comes to COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)